Article by: SPfreaks

Interview by Monita Rajpal, CNN

SPfreaks is happy to present the full transcript of this interview to you, as provided by CNN Transcripts. Images are screenshots from the interview.

TALK ASIA – Interview with Billy Corgan (Aired August 23, 2013 – 05:30:00 ET)

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

Monita Rajpal, Anchor, CNN International (voiceover): It was one of the biggest bands of the ’90s. Known for their angst-ridden and dreamy songs, The Smashing Pumpkins are still drawing in crowds by the thousands, some 25 years after their debut.

Founded by lead singer-songwriter, Billy Corgan and Guitarist, James Iha, their first album reached gold status. But the follow-up, “Siamese Dream”, fared even better. Thanks, by and large to the song, “Today”, which peaked at number four on the alternative rock charts, solidified their status as rock stars.

It was their third album, though, that would see the band truly skyrocket. “Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness” sold more than nine million copies with four singles hitting the pop charts, including “1979” and “Tonight, Tonight”.

After a drug overdose killed the band’s touring keyboardist and led to the arrest of drummer, Jimmy Chamberlin, in 1996, the remaining band battled on to make two more albums.

Both failed to produce a single that would chart higher than “Ava Adore” at number 42 on the U.S. Billboard charts. And in 2000, Billy Corgan announced the end of The Smashing Pumpkins.

Seven years later, Corgan resurrected the band with new members. Today, they’re back on the road with a new album and throngs of loyal fans.

This week, on “Talk Asia”, Billy Corgan shares the drama and dysfunction of one of alternative rock’s most influential bands.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

RAJPAL: Billy Corgan, welcome to “Talk Asia”.

WILLIAM CORGAN, SINGER-SONGWRITER AND FRONTMAN, THE SMASHING PUMPKINS: William now.

RAJPAL: William Corgan.

CORGAN: William Corgan.

RAJPAL: When did that change?

CORGAN: I’ve been morphing for a while, so –

RAJPAL: Really?

CORGAN: Yes. I’m going to go William now.

RAJPAL: Do you feel more serious?

CORGAN: No, no. It’s just – that’s actually my birth name.

RAJPAL: Do you feel more grown up, though?

CORGAN: No. Just “Billy” gets uncomfortable at some point.

RAJPAL: Really?

CORGAN: Like, wrinkles and Billy – it just doesn’t work.

RAJPAL: Well, William –

CORGAN: Thank you.

RAJPAL: — The Smashing Pumpkins have finally made it to Hong Kong. What took you so long?

CORGAN: I don’t know, you know, it’s a weird world. Because, you know, I’ve been to Thailand and, you know, other places in Asia. And why we never came here, I don’t understand.

RAJPAL: Yes. What do you believe has been the means to the success or the longevity of The Smashing Pumpkins? I mean, we look back from the formation in 1988 to, you know, “Gish” in ’91 and now, “Oceania” today. What do you think has been the means for its longevity?

CORGAN: Well I have a saying, which is, “Crazy is good for business”. I think rock and roll really is about being a bit crazy. And that sounds like a line from a Scorpions song, but – like, “Crazy”.

(LAUGHTER)

CORGAN: It’s not a corporate thing. It’s been turned into a corporate thing, but really, people like me – you can’t invent people like me. We kind of come out of weird places and strange backgrounds and we can’t be sort of prototyped or copied. Although we can be imitated, we can’t be copied.

So I think that’s really what it is. I mean people – in essence, they have to go to a live band event to see this one-of-a-kind thing. And it’s no different than King Kong, you know, in chains. Like, “Rrrr”. You know, that’s how I feel sometimes. I mean, there I am. I’m a flawed thing, but there’s only one of me. And if you want to see that one of the thing, there it is.

RAJPAL: Did you always embrace that uniqueness?

CORGAN: No. Nor do I now. But, you know, like, when I was young, I hated my voice because it was so strange. And my father has a very strange voice, too. So it would be like, “Wow, why do we have these weird voices? Like, shouldn’t we have more normal voices and stuff?” But then you realize that that’s at the heart of identity.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Which, in a world of, kind of a lot of imitation – and you see imitation in fashion – all levels of culture. So to have any level of distinction in a world that’s really intent on copying is actually a blessing. But for years, it felt like some sort of weird curse.

RAJPAL: When we look at your album, “Oceania”, do you think it’s an album that you could have made, say, 20 years ago?

CORGAN: No, nor would I have wanted to. Because different circumstances at the beginning of what’s called the grunge era. It was really about sort of stimulating an audience and the mosh pit was probably the most important factor on whether or not a crowd was considered a good thing or a bad thing. So you’re making music to kind of create this propulsive, kinetic environment. You’re not writing songs for people to get married to. That sort of happens later.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: If you would have asked me, you know, the 20-year-old me, about the kind of album I’ve made on “Oceania”, the 20-year-old me says some of it’s boring. But sometimes it takes those spaces and those kind of quietude to find something else. And I think we all go through that as we get a little bit older – we look for sort of different simplicities. And there’s a simplicity in “Oceania” that my earlier work doesn’t have. Where I was so intent on constantly proving something.

RAJPAL: I’ve read that you came to writing the album –

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: The album, itself – I understand it’s supposed to be this – taken in its entirety, as a journey – not just as singles. But there are –

CORGAN: That’s kind of a press line. But I – I’m glad you read that, but –

RAJPAL: But in –

CORGAN: It’s kind of a – honestly, it’s kind of a bull-[EXPLETIVE DELETED] press line.

RAJPAL: Really?

CORGAN: Yes, because, in this day and age, you’re sort of forced to make a comparative reason – like why even bother making an album?

RAJPAL: Sure.

CORGAN: And so we were like, “Well, we’ve made something – you’re kind of forced to listen to the whole thing or you’re not going to get it”. And people actually, then, listened to it.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Because if you follow in the other culture, it’s really about just trying to come up with 12 singles.

RAJPAL: When you look at – I guess I read that you came – you approached it from actually a place of being happier than you have been in a while.

(LAUGHTER)

RAJPAL: Is that –

CORGAN: Did I say that?

RAJPAL: Was that not true?

CORGAN: No, no, that’s true.

RAJPAL: Does that, in itself, pose challenges, when it comes to songwriting?

CORGAN: There’s a long established concept that gets bandied about, which is “Misery makes for great art”. And I actually think this is – if we were asking a Shinto Monk, I think they would laugh at this idea.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Because you’re basically saying, “Suffering’s good for business”. And I don’t think suffering’s good for business. Crazy’s good for business, suffering isn’t. I think suffering or the gestalt of, “Here I am, ripping my heart open” – I think that lasts for about two or three albums.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: At some point, you have to mature into the deeper work. Most people are living lives of sort of survival. And constantly posing an existential crisis, either through fantasy or oblivion, really has been pretty much explored in rock and roll. At least in the western version of rock and roll. Maybe not over here in Asia, but we’ve sort of, kind of, been through all that.

RAJPAL: So what are you exploring now?

CORGAN: God. I once did – a big American magazine was doing a thing called, “The Future of Rock”.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: And, you know, they asked 50 artists, “What’s the future of rock?” And my answer was, “God”. And they said, “What do you mean?” And I said, “Well, God’s the third rail of -” What is it? “Social security is the third rail of politics in America”. Well, God is the third rail in rock and roll. You’re not supposed to talk about God. Even though most of the world believes in God. It’s sort of like, “Don’t go there”.

I think God’s the great, unexplored territory in rock and roll music. And I actually said that. I thought it was perfectly poised. And, of course, they didn’t put it in the interview.

RAJPAL: What would you say to Christian rockers, then?

CORGAN: Make better music.

(LAUGHTER)

CORGAN: Personally, my opinion – I think Jesus would like better bands, you know?

(LAUGHTER)

CORGAN: Now I’m going to get a bunch of Christian rock hate mail.

RAJPAL: But that’s interesting –

CORGAN: Just wait, here’s a better quote –

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Hey, Christian rock, if you want to be good, stop copying U2. U2 already did it. You know what I mean? There’s a lot of U2-esque Christian rock.

RAJPAL: Sure.

CORGAN: Bono and company created the template for modern Christian rock. And I like to think Jesus would want us all to evolve.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

RAJPAL (voiceover): Coming up, Billy Corgan reveals the sad inspiration behind one of his newest singles.

CORGAN: Well, I had two losses. Losing her as a mother and losing her as a friend.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CORGAN (singing): When they locked you up they shut me out/But gave me the key so I could show you round. /Yet we were not allowed. /Omens of the daydream. /But caught as you’re bound in Thorazine.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

RAJPAL: I’m curious about the single, “Pale Horse”.

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: And I was wondering what the origin of the title of “Pale Horse”. Was it – did it come from, and this is just my interpretation – but did it come from the –

CORGAN: It’s like “Trainspotting”.

RAJPAL: The New Testament –

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: The Bible – the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – the last horse is Pale Horse.

CORGAN: I had no idea.

RAJPAL: — Which symbolizes death.

CORGAN: Had no idea. But, in your sentient intuition, what you did pick up on is that it’s a song about my mother.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: And it’s really about the point where my mother left my life around four years old (ph). So it is really reflective of death. Symbolic –

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: — not literal. And, of course, she later died when I was 29, from cancer. So I had two losses. Losing her has a mother and losing her as a friend. So, yes, the song sort of deals with that. But I had no idea. But that’s interesting how the unconscious works, so –

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: I’ve never been a big bible reader, so –

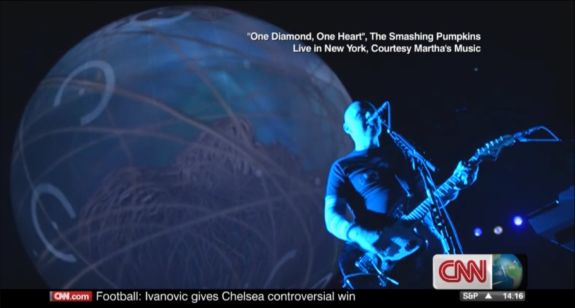

RAJPAL: Well, neither have I, but I just was curious about “Pale Horse” and the origins of that. Another single that I really liked in “Oceania” was “One Diamond, One Heart”.

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: It’s beautiful.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CORGAN (singing): However you must fight/Within your darkest night/ I’m always on your side. /Lovers as lonely as lanterns lost.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

RAJPAL: There’s a line in it that says, “However you must fight, within your darkest night, I’m always on your side”. How hard do you think you’ve had to fight to actually get to this point where you are now? Actually, perhaps, in a different place – in a potentially better place?

CORGAN: Oh, yes. Yes. The great thing about rock and roll is, if you want to fight – like, fight the system, fight the man, fight the government, fight the people in front of you – it’s Don Quixote all over again. You’re really chasing windmills. And then the business sort of is predicated on creating a competitive atmosphere, where you want to obliterate your competition, because it sort of engenders more sales.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: And people start doing stupid stuff – stunts and –

RAJPAL: Did you buy into that?

CORGAN: You do on some level. I grew up in sports, so it sort of always made sense to be competitive. Like, if you’re going to try to dunk on me, I’m going to dunk on you.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: And there’s something beautiful like, you know, you read about how the Beatles and Stones would sort of take turns trying to get the number one song. I don’t think there’s anything bad with that. But realistically, artists are really in a race with their own ability. And if you too much focus on the culture – the culture’s always going to give you the wrong information. It’s been proven time and time again that cultures really don’t know what they want. Hence, you know, great artist like Johnny Cash dies, and everyone’s like, “Oh my God, Johnny Cash was great”.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Well, I bet if you look to Johnny Cash’s career, there are about 30 years, there, where people weren’t paying a lot of attention to Johnny Cash. Why didn’t they pay attention to him all along? Well, they were busy doing something else or they were fascinated with this trend, or something. And then we realize, “Wow, what a great treasure Johnny Cash was, not to American culture, but to the entire world”. Ultimately, the public’s going to abandon you, the record company’s going to turn on you at some point when you don’t sell enough – so it’s really an integrity game.

RAJPAL: How do you keep your integrity?

CORGAN: You have to have a root of some sort of belief system. And, for me, you know, I sort of work on the love concept, which is, you know – is what you’re doing engendered of love or is it engendered of some sort of material construct? And I think there’s plenty of evidence to prove that material constructs fail.

RAJPAL: Did it start out that way, when you created the band? Did it start out?

CORGAN: No, no. I wanted to get the [EXPLETIVE DELETED] out of my city. And it wasn’t even – it was like the Wizard of Oz – sorry for the swear.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: I wanted to get the heck out of my city. It was like “The Wizard of Oz”. I just wanted to get on the Yellow Brick Road and get somewhere.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Because where I was, was just so, like, I mean, you know.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: So leaving is a conceptual thing. Fighting the thing out there – the dragon out there- – it’s all conceptual. But if you don’t have the spiritual background, the cultural background, somebody doesn’t find you at an age and say, “You’re talented, you’re special” and get you in a system that’s going to support you.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Rock and roll is basically, you know – it’s a system of exploitation.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: And I hate to use the word because it’s honestly disrespectful, but it’s a slave system. It’s an indentured sort of slave system where they kind of lock you in and then they play tricks with your mind and try to get as much out of you, predicated on the idea that you’re only going to last four or five years.

RAJPAL: But that system –

CORGAN: Yes?

RAJPAL: — did get you recognized. Did get you –

CORGAN: Did it?

RAJPAL: Didn’t it?

CORGAN: Where are all my fans? There’s no one waiting in the lobby over there.

RAJPAL: Security.

CORGAN: I don’t see anyone waiting over there.

RAJPAL: But they have been. They’re coming to see you.

CORGAN: No.

RAJPAL: They’re going to – you sell tickets.

CORGAN: Yes, that’s just.

RAJPAL: People still buy your albums. People still know who you are. Your music was heard.

CORGAN: It’s meaningless.

RAJPAL: Really?

CORGAN: It’s meaningless. The only thing that means anything is what you create. That’s where the great Beatle line, you know, “The love you make is equal to the love you take”. Or I always get it wrong. But I mean, that’s really what it is.

So my experiences in music really have to do with the people I’ve met, the things I’ve seen, the ability to absorb different cultures, different ideological frames. Come in contact with people who have no relationship to “Gilligan’s Island” and the silly, weird ’70s world that I grew up in.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: It’s fantastic. It’s a spiritual education. And what I’ve created out of that journey is the value. Whether anybody gets it or doesn’t – that’s really, honest, inconsequential.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

RAJPAL: So we have this side of William Corgan.

(LAUGHTER)

RAJPAL: Then we have the other side as well –

CORGAN: She’s a very good interviewer. I like her.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CORGAN (singing): Believe in me, believe, believe/ That life can change that you’re not stuck in vain./ We’re not the same, we’re different./ Tonight, tonight, tonight/ So bright/ Tonight.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

RAJPAL: So, when you look back at the albums that you have created.

CORGAN: Yes?

RAJPAL: Such as multi-platinum albums like “Siamese Dream” –

CORGAN: Right.

RAJPAL: “Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness” – what are your interpretations of that time, now?

CORGAN: I see them as faithful postcards to where I was. And they are inherently beautiful for what they express in their limitations.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: But I see them as limited within their moment.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: But it’s also the culture’s moment, too. So, for example, you listen to music from the early ’90s, there’s idealism. You listen to music by the end of the ’90s, that idealism is gone.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CORGAN: Today is the greatest/ Day I’ve ever known. / Can’t live for tomorrow/ Tomorrow’s much too long.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

RAJPAL: Songs like, “Today” –

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: From “Siamese Dream”.

CORGAN: Right.

RAJPAL: “1979” from “Mellon Collie”.

CORGAN: Right. I did write those.

RAJPAL: “Zero”.

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: Those kind of songs –

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: — those are important indicators of the certain emotion that was – at least that you felt, at that time.

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: What are your memories of your life at that time?

CORGAN: I was miserable. I was totally miserable. So I was operating off of more of an idealism. Like, who I wanted to be or who I wished I was.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Because who I really was or how I felt I was, was miserable. Because I had no frame by which to deal with the situation I was in.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: I was in an unhappy band. I’d sort of found whatever I needed to find and – but it wasn’t this magical thing I thought it was going to be.

RAJPAL: What about, then, the success of those albums? Like, I love “Siamese Dream” –

CORGAN: Well, they were good.

RAJPAL: Well, you were happy with that, though, right?

CORGAN: Yes, but you could argue that the success of those albums is very much a communication between two limited perspectives. So if you make dumb music for dumb people and dumb people buy it, it doesn’t mean it’s good.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Well, if you make repressed, middle class, white, suburban, existential crisis music and a bunch of people just like you buy it, is that success?

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: I mean, yes, it’s success in the form of communication. But is it success in being true? No, it’s not true. It’s true to its corner, but it’s not true.

RAJPAL: Where does this need to –

CORGAN: Ruin my career?

RAJPAL: –search – no. No, no. To search and seek these kind of answers – come from?

CORGAN: I don’t know. I think you’re just born with it. What do they say in America? You have a high BS meter. You know what I mean?

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: Yes, I stopped going to the – you know, I was raised Catholic and I stopped going to church when I was eight. Because I was like, “What is this?”

RAJPAL: So, you know, there are some shrinks out there who would say –

(LAUGHTER)

RAJPAL: — and bear with me for this one –

CORGAN: Have you been to a shrink?

RAJPAL: Well, haven’t we all? There’s some shrinks out there who would say that the people that we are connected to, or we find ourselves connected to, are there to help us reconcile certain issues or –

CORGAN: Karmic wounds.

RAJPAL: Yes. And the people that we are most intimate with, whether our partners, band mates – they are there to help you recognize and work though those issues.

CORGAN: Right.

RAJPAL: Is that what The Pumpkins were for you? The original band?

CORGAN: No.

RAJPAL: No?

CORGAN: No, we were four strangers who agreed on a musical vision. And we did more harm than good.

RAJPAL: In what way?

CORGAN: It was destructive.

RAJPAL: But then, some could say, well, if you look back at your – say, when you were growing up – same kind of dysfunction, right?

CORGAN: True, true.

RAJPAL: What did you learn about yourself in that experience?

CORGAN: Which one?

RAJPAL: The first band experience.

CORGAN: I would say the key experience for me, from the original version Smashing Pumpkins was, “What is loyalty?” What is loyalty? Because I had a false concept of loyalty and I rode that ship all the way to the bottom. When most people wiser than I, would have jumped off the ship when it was to their benefit.

So people always say, “What’s your greatest career regret?” It’s when the band blew up in ’96, that I didn’t jump off and make a new ship. I rode that ship all the way to the bottom. Like, literally, until it was like the bubbles were coming up and I was sitting there like –

RAJPAL: Is it kind of like, you know, when you’re staying in a bad relationship, that you’re always hoping that something will change. That things will work out in some way, shape, or form.

CORGAN: Yes. I’m sure you’ve only had successful relationships, but I mean, if you’ve ever been there where you’re breaking up with somebody for the ninth time –

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: And you’re like, “Ok, this is real”, right? You know.

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: We did a lot of that. We didn’t really break up so much as we were like, “OK, now it’s going to be like this, or it’s going to be like this”. And then, of course, nothing would change.

RAJPAL: What about when it comes to what you learned about yourself from your family?

CORGAN: False loyalty.

RAJPAL: Again?

CORGAN: I think a lot of people really struggle with false loyalty.

RAJPAL: I read that your dad said that you’d saved his life? On many occasions?

CORGAN: He’s being generous.

RAJPAL: That there was an article where he was quoted as saying that, “I grew up in a house of no love or emotion and it kind of sticks with, you end up passing it on to your kids”. Is that -?

CORGAN: That’s fairly accurate.

RAJPAL: Really?

CORGAN: Yes. Accurate.

RAJPAL: Your dad was a musician.

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: Still?

CORGAN: No, he doesn’t play anymore.

RAJPAL: did you ever want to be like him?

CORGAN: Oh yes. My father was my idol.

RAJPAL: Really?

CORGAN: Yes, I wanted to – I mean, this bad posture I took from him, too. He’s very charming. He, you know, was very handsome and I mean, he looked and moved like a rock star, so –

RAJPAL: When did you finally feel – or have you – a sense of stability in your life?

CORGAN: Never.

RAJPAL: Never?

CORGAN: Never. No. I’ve invested in one particular concept and it’s – I would say as we – it’s a wash. I’m happy to have done what I’ve done and I feel privileged to have communicated. Blessed to have been recognized, where many people don’t –

RAJPAL: Yes.

CORGAN: But yes, personally devastating.

RAJPAL: What do you think will be your legacy?

CORGAN: I think I’m a radical. I think I’m an artistic radical and I think I’ll be recognized as one. I’m a really good musician and a songwriter, but I think my real legacy will be as a radical. I am a radical in an era when there are very few radicals. In my business – I know there’s plenty in other places. But in my world, which is supposed to be full of radicals, there’s actually very few.

RAJPAL: So we have this side of William Corgan –

(LAUGHTER)

RAJPAL: Then we have the other side as well –

CORGAN: She’s a very good interviewer. I like her.

RAJPAL: — where we have the tea-drinking, tea shop-owning, and pro- wrestling-loving man.

CORGAN: Boy-child.

RAJPAL: Very different elements. Or are they the same?

CORGAN: Same.

RAJPAL: Pro-wrestling — what’s that about?

CORGAN: It’s fun.

RAJPAL: See? You do have fun.

CORGAN: Yes.

RAJPAL: Really?

CORGAN: In quiet moments. When no one’s watching.

RAJPAL: William “Billy” Corgan –

CORGAN: This is where you say, “Goodbye”.

RAJPAL: Thank you for your time.

CORGAN: Sure.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

END

Leave a Reply

The interviewer, Monita Rajpal, announced beforehand that Billy (William) was going to say something about having a child wish; that quote didn’t make the final cut obviously? Pretty good interview nevertheless!

An interesting read.

Thank you!